Writings on the Walls: The Hidden Poetry of Angel Island

A brief history of Chinese immigration to the US, told through the voices of those who were really there.

Growing up in the United States, one major component of our history curriculum at school was learning about the existence of two islands: Ellis Island and Angel Island. One processed new immigrants arriving to the US via the east coast, and another did the same for the west coast.

But the reality of these two islands is less neutral than it might seem. Because while Ellis Island was mainly meant to welcome new immigrants in, Angel Island was created to keep them out. And even today, Angel Island continues to speak out with the voices of Chinese immigrants who were detained there decades ago — through the poetry inscribed on its walls.

The Immigrant Experience

Between 1910 and 1940, Angel Island was active as the main processing center for new immigrants arriving in the United States via the west coast. The island was perfectly situated to take over the processing of immigrants (as the previous solution was an overcrowded warehouse in San Francisco). Much like the nearby Alcatraz Island (the famed prison), Angel Island is surrounded by water, preventing potential escapes to the mainland.

Out of the one million immigrants who were processed over the decades, the majority were Chinese and Japanese, but there were also people arriving from Russia, India, and Central South America. Most of the Chinese immigrants were boys aged 14-18 hailing from the Canton region in southern China, an area that was impoverished from the Opium War. For the 30 years that Angel Island was in use, about 100,000 Chinese people were detained in its walls.

Temporary detention may not sound that unreasonable when it comes to processing boatloads of new immigrants, but the immigrant experience on Ellis Island versus Angel Island looked quite different. On Ellis Island, European immigrants could be expected to be processed in a number of hours (and occasionally days). By contrast, on Angel Island, this processed looked more like weeks, months, or years — with the longest detention lasting a whopping 756 days.

Why keep people detained for so long? Unlike on the east coast, immigrants were often subject to intense interrogations to confirm their identities. This could include minute questions about the layout of their home villages (“who lived in the house on the third row second to the right?”), the number of steps from one place to another inside their house, and detailed family histories. If they tripped up, authorities could justify sending them back across the Pacific.

Additionally, to cross-reference their answers, officials compared their subjects’ answers between interviews and sought out family members in the US to confirm their stories. For immigrants who were joining their family members on the west coast, this process could be a little shorter. But for authorities to reach family members in Chicago or New York, it could easily take months for them to corroborate the details.

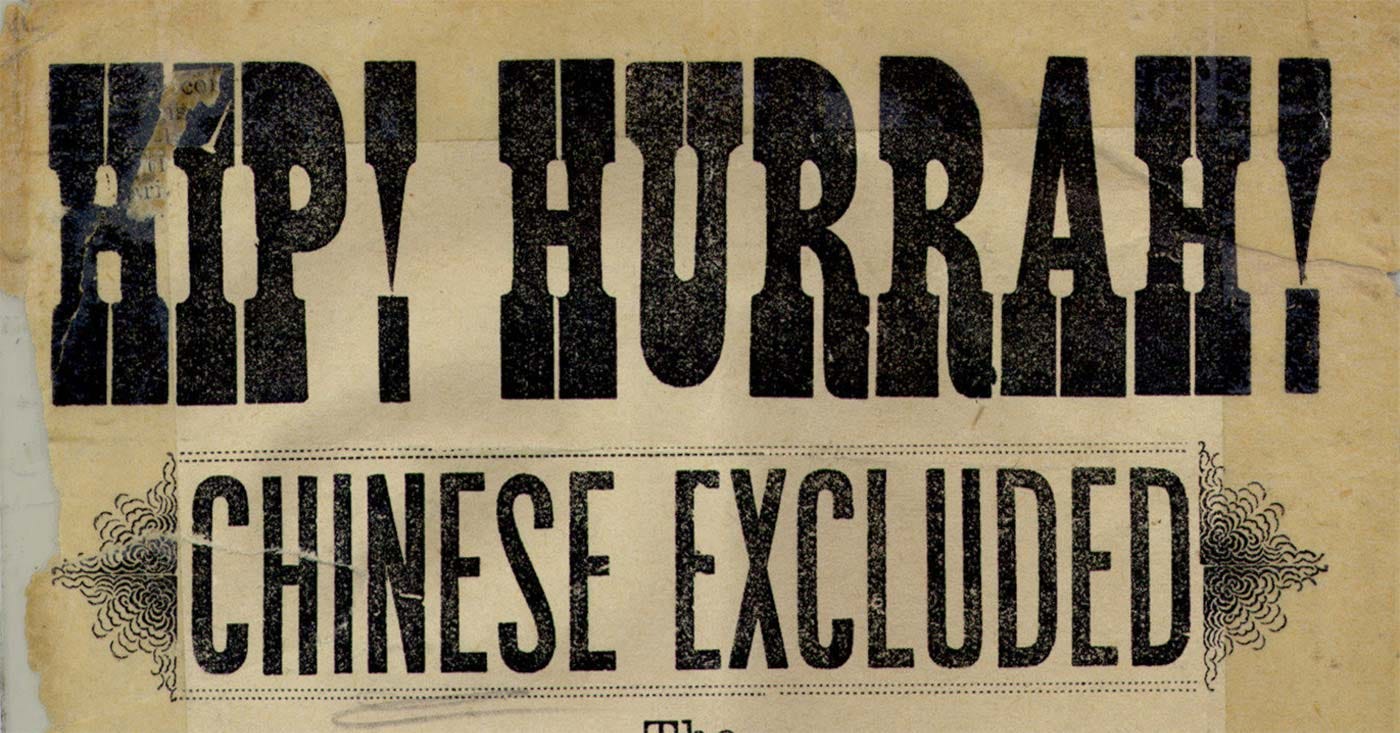

So why did all this fact-checking matter in the first place? For Chinese people in particular, immigration was heavily restricted due to the Chinese Exclusion Act, a period of US history that lasted a whopping 61 years. Passed in 1882, this act banned Chinese laborers from entering the country and prevented the naturalization of Chinese immigrants. Originally, this period of time was supposed to end after 10 years, but in 1892, Congress renewed the act and extended it indefinitely.

This eventually wasn’t just limited to Chinese people. In 1917, the Immigration Act expanded exclusion laws to include Japan, India, and most of Southeast Asia. This was followed by another Immigration Act in 1924 which banned all immigrants who were ineligible for citizenship. These policies continued until 1943, when China became an ally during WWII. (It’s all about politics, baby.)

So, during the time that immigration was so heavily restricted, how could Chinese immigrants and Asian immigrants in general enter the country? This can be largely explained through the “paper sons” phenomenon. One group of people that were permitted to enter the country was relatives of citizens already in the United States. And the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire (which destroyed most city records — including birth certificates) created a convenient opening for new immigrants to claim “paper” relation to current residents.

To enter the country, immigrants would assume identities that tied them to Chinese families and citizens in the United States, memorizing facts about their family and their life. When US officials started catching on, they started viewing new immigrants with stricter scrutiny.

Aside from repeated, intense interview process for new arrivals, immigrants were also subject to embarrassing and shameful health examinations. They were often stripped and examined for diseases or underlying conditions, and forced to provide blood (and sometimes stool) samples to search for parasites.

Not only that, thanks to the Page Act of 1875, which specifically banned "immoral Chinese women" from entering the country, women who arrived on Angel Island had an extra dose of interrogation questions regarding their sex life. Even after these ordeals, 18% of applications were ultimately rejected - that's about one in five people who arrived on the west coast (compared to Ellis Island, where only about 2% of applicants were rejected).

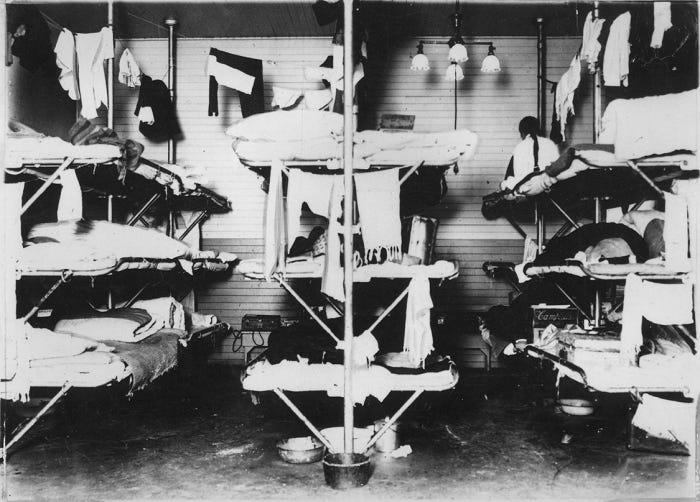

Depending on nationality, not all detainee experiences were the same, but the Chinese experience in particular was marked by a deep sense of hopelessness, fear, and anger. They spent the majority of their time confined in crowded barracks which were often overcrowded and unsanitary, squeezed into three tiers of small metal bunks which often gave no room to move when the barracks were full. For many, Angel Island didn’t feel like an impermanent, transitory stage: it felt more like a prison.

The Poetry of Angel Island

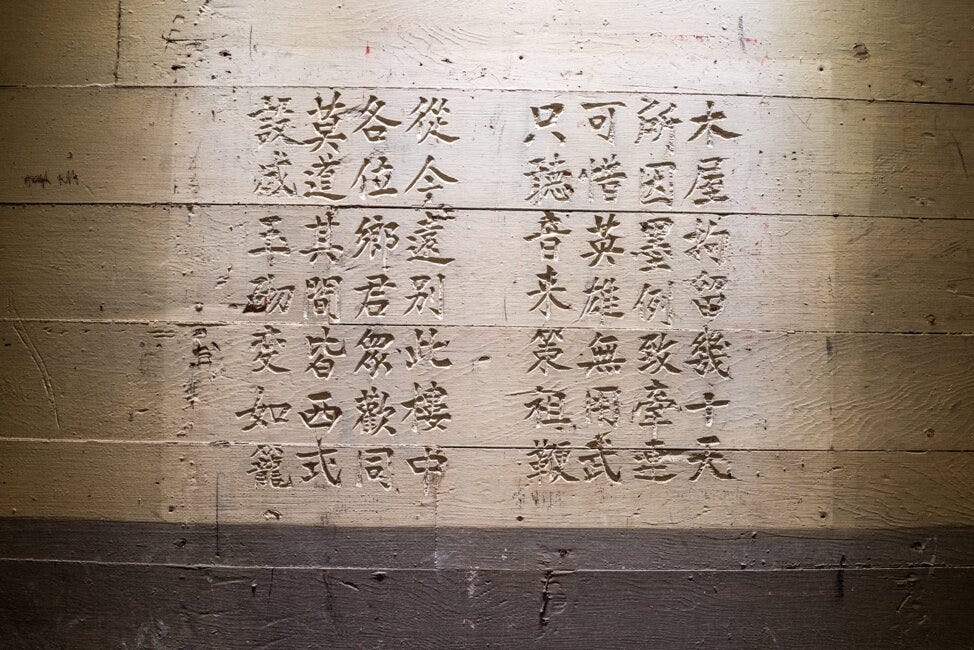

Angel Island Immigration Station closed in the 1940s, and its original buildings were scheduled to be torn down in 1970. But before demolition took place, park ranger Alexander Weiss discovered what seemed to be writing inscribed on the walls of the men’s barracks.

When his boss dismissed the writings as mere graffiti, Weiss informed a local professor, George Araki, of his findings. Araki visited the buildings and determined that it wasn’t just graffiti, but was actually Chinese poetry, written by the men who were detained at Angel Island.

(Many of the poems were found in the men’s barracks; this is because the women’s barracks had burned down before the discovery was made. It was also originally thought that the women's barracks wouldn't have had any poems anyway because many Chinese women at the time were illiterate, but former female detainees claim that they saw and wrote poems on the walls as well.)

These poems are not just whimsical verses: they take the form of classical poetry from the Tang dynasty. Most of the poems are four, five, or seven characters per line, with alternating lines rhyming. Written in ink or carved directly into the wood walls, these poems documented the experiences and frustrations of the people who were facing the traumatic experience of confinement. Officials weren’t a fan of the wall carvings, and would regularly fill up the poems with putty and paint them over. As a result, many of these poems have been lost, but today, over 200 have been discovered.

These poems contain messages of deep grief and pain, longing for what once was, and longing for what seems so close yet so out of reach. Most of them are unsigned, but some contain names and/or hometowns of the authors. They contain stories of the journeys that they took to get to the United States, the words of their family members before they left, and contain allusions to Chinese folklore and mythology. Some pay tribute to those they met while they were being detained, or contain messages for future arrivals. (You can read a selection of the poems along with their English translations here.)

The above poem contains a plethora of classical Chinese allusions. First, the jingwei is a Chinese mythological bird who drops gravel into the ocean in an attempt to fill it up (prior to her transformation into a jingwei, she was a human who drowned in the sea). Ziqing refers to Su Wu, who was detained for nineteen years by the Xiongnu during the Western Han dynasty. And Ruan Ji was a Three Kingdoms period scholar who would weep before returning home after his excursions into the mountains.

Keep in mind that many of these immigrants would not have spoken Mandarin as their mother tongue. As the majority hailed from southern China, languages such as Toishanese and Cantonese were much more common. (Some might call these “dialects”… but that’s an article for another time.) In this video you can hear one of the poems being sung in Toishanese as an improvisation on a folk song called a muk'yu (or wooden fish) from Toisan.

Aside from the poems that were physically found on Angel Island, two detainees in the 1930s, Jann Mon Fong and Tet Yee, copied down poems and snuck the manuscripts into San Francisco upon their release. These poems were compiled in a book called Island, which was originally self-published by three Asian-American historians. Their most recent edition also includes similar Chinese poems that were found on Ellis Island and in Victoria.

A Mirror into the Present

While these poems may seem like a tale from the past, their stories are really not so long ago. And the experiences and trials that these people faced have been repeated throughout history, even up until the present day. Around the same time that Chinese exclusion was lifted in 1943, Japanese-American citizens were forced into internment camps (a non-military necessity largely fueled by bigoted rhetoric which wormed its way straight into the highest ranks of the US government, and may very well be the subject of a future article).

Furthermore, immigrants to the United States today are still experiencing the same fear, isolation, and hopelessness that many of the detainees on Angel Island experienced decades ago. In 2019 alone, over 500,000 people were detained in more than 200 ICE detention centers around the United States. It’s not difficult to see the same problems, even amplified: overcrowding, unsanitary conditions, holding detainees for long periods of time, and separating family members. In fact, since 2003, over 200 people have died in ICE detention centers.1 This is a blaring violation of human rights that, for the Asian-American community in particular, sounds heartbreakingly familiar.

Thanks for reading!

I first covered this topic in a YouTube channel that I launched at the start of the pandemic, but which has since been paused (mainly because video creation is personally way more time-consuming compared to writing). But who knows what the future holds, right? So if the content of this newsletter felt familiar to you, then you are most definitely a real one. Thank you for supporting all my creative endeavors :’)

I’d also like to give a formal shoutout to two other Substack newsletters that I’ve been enjoying. First, Mathias Barra, author of The Average Polyglot, featured my article on Gouin in his most recent newsletter! He writes a great weekly newsletter that spans from language learning advice to deep dives on lesser-known languages around the world. I’d also like to recommend Joel Neff’s newsletter Learned, in which he investigates the words that we encounter in everyday life, plus not-so-ordinary words (with a humorous spin). Both of these newsletters will definitely be of great value if you are a language learner or language fan in general, and I highly recommend subscribing to both.

Finally, if you enjoyed this article, would you consider subscribing to this newsletter? It supports me a lot and I always love getting to know my new subscribers!

Thanks for reading, and I’ll see you next week!

Immigration Detention 101. (n.d.) Detention Watch Network. https://www.detentionwatchnetwork.org/issues/detention-101

Ahmed, B. (2017, Feb 22). The Lost Poetry of the Angel Island Detention Center. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/the-lost-poetry-of-the-angel-island-detention-center

Diao, Y. (2017, May 3). Echoes of History: Chinese Poetry at the Angel Island Immigration Station. Smithsonian Folklife Festival. https://festival.si.edu/blog/echoes-of-history-chinese-poetry-and-the-angel-island-immigration-station

Goh, T. L. (2019, Jan 13). The Walls Speak: Excavating the Chinese Immigration Experience at Angel Island. Los Angeles Review of Books. https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/the-walls-speak-excavating-the-chinese-immigration-experience-at-angel-island/

History of Angel Island Immigration Station. (n.d.) Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation. https://www.aiisf.org/history

Lanzendorfer, J. (2018, Dec 4). The Talking Walls of Angel Island. Los Angeles Review of Books. https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/talking-walls-angel-island/

Lee, Y. and Yung, J. (2015, Sept 23). Angel Island Immigration Station. American History. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199329175.013.36

Snyder, N. (2019, Jun 19). Poetry on the Barracks Walls of Angel Island. Book Riot. https://bookriot.com/angel-island-poetry/

Really enjoyed this one, thanks for sharing these poems.

Having been born in France, I never learned anything about Angel Island so this was very interesting! I read "When the emperor was dive" (by Julie Otsuka) last year about a Japanese family being sent to an internment camp so it's very enlightening to hear about what happened to the Chinese immigrants as well.

Also, thanks for your mentioning me! :)