When Immersion Becomes Submersion: The Consequences of Bad Language Policy

How Arizona's longstanding English-only education law is still hurting students today.

When I was an undergraduate in Arizona, I spent a good portion of my time in school being confused about what the heck I should major in. (At one point, I went through the ENTIRE list of majors that my school offered and wrote down anything that even vaguely interested me. I was a confused kid.)

During my sophomore year — in the midst of this chaos — I took a course called “foundations of structured English immersion,” a requirement for anyone working towards a teaching license in Arizona (since I figured that might be my path at some point). We mostly learned ways to support English language learners (or ELLs) in our future classrooms, plus some Arizona-specific laws regarding ELLs.

But the one thing that they didn’t tell me — and I wouldn’t realize it until about two years later — is that Arizona’s policies for supporting ELLs in schools are actually pretty terrible. And that’s a crucial thing for any incoming teacher, or anyone who cares about students in general, to understand.

So, what exactly is Arizona’s policy? How does it affect learners, both linguistically and non-linguistically? And what is the potential impact of bad language-in-education policy?

The policies that inform it all

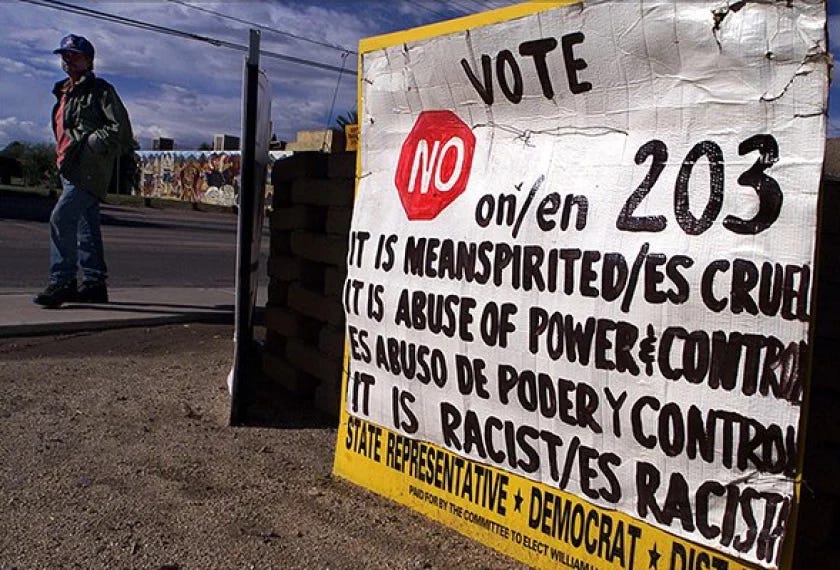

In 2000, Arizona voters passed Proposition 203, which established an “English-only” rule in Arizona public K-12 schools. This consequently led to a ban on bilingual programs as well. Proposition 203 was fairly vague (and passed by a simple majority of voters), so the details were later fleshed out by HB 2064, which defined the SEI model (or, “structured English immersion”) for teaching ELLs in Arizona. It was implemented statewide in 2008, and has been in place ever sense.

While ELLs may seem like the minority in the classroom, these laws do not just affect a small number of students; in fact, 1 in 8 Arizona students is an ELL. And out of this population, an overwhelming majority of ELLs are Spanish speakers, at 86%, followed by Navajo speakers at 8%.1 So this policy has had a major impact on the lives of thousands of Arizona students (not to mention, disproportionally affects Latino students).

What is SEI?

So, what exactly is “structured English immersion”? And what is it meant to do?

SEI is a method of language instruction in which (at least in the state of Arizona) ELL students are pulled out of the classroom for a few hours a day to participate in intensive English-only language instruction. Initially this SEI block took up four hours (that’s about 2/3 of the school day!!!), but it has since been reduced.

Advocates of SEI insist that within a year, ELLs will have gained enough language abilities to successfully return to the mainstream classroom. But in reality, this (financially convenient) miracle method of language learning is not backed by any real pedagogical substance or language acquisition research. And over the last few decade and a half of its existence, it has ended up hurting ELLs much more than it has helped them.

To dissect this, we’ll examine two dimensions of SEI: the time constraint SEI imposes on language learning, and the English-only policy.

SEI and “picking up language” quickly

SEI seems enticing for many reasons. It banks on the idea that kids can soak up language if they learn it intensely for a year. But SEI is predicated on an impractical and ineffective view of language acquisition.

First, it is incredibly unrealistic to assume that kids will be able to “pick up” language in just one year, achieving equal fluency to students in the mainstream classroom. It is a common fallacy to believe that children are naturally gifted with the skill to pick up any language to the extent that they can do it with minimal effort and high speed.

In fact, current language acquisition research has shown that children’s language learning is not quick and painless — but rather, is slow and effortful. (For more on whether children are better language learners than adults, check out my previous article here.)

And on top of that, a long-term study of ELLs in the United States demonstrated that the minimum amount of time that of time it takes for ELLs to reach grade-level performance in their second language is four years.2 This means that a short-term solution, like pulling students out of the classroom for a year and expecting them to just "pick it up" quickly, will ultimately prove unsuccessful for supporting effective language acquisition.

The English-only ban

A second misguided component of SEI is the assumption that English-only instruction, partially characterized by the word “immersion,” is the most effective way to learn. While English-only immersion sounds enticing and promising, SEI is not real immersion education — more accurately, it’s “submersion.”

Don’t get me wrong — I do believe that immersion programs can be a legitimate and effective way to teach a language. But for an immersion program to actually be effective, it will likely look nothing like what ELLs in Arizona are experiencing. With SEI, learners are rarely intentionally and methodically supported to learn a new language at school. Often times, the reality is this: they’re drowning.

So what do successful immersion programs look like? Generally speaking, they are well-resourced and highly scaffolded, meaning that they put intentional supports in place to help learners along the way. Teachers are trained to introduce language in a way that makes sense for new learners — students’ aren’t just “soaking it in” while fluent speakers speak rapidly about a range of unfamiliar topics around them.

And even in an immersion context, teachers will draw heavily on students’ first languages to make sure that new language is being introduced in a principled way (and, that students are actually comprehending the subjects that they’re learning — it is a school, after all). Successful immersion programs will take into account learners’ first languages and draw from them as a resource. And no legitimate immersion program could claim that their students will become fluent speakers in a year. Language learning is a timely, effort-filled process, after all.

It’s not just about language learning

But we can’t talk about this topic without acknowledging our context — that these kids are in schools, and will need not just linguistic support but also academic and content-based support as well.

It may be a surprise that research in language and education over the last few decades has consistently shown that one of the biggest indicators for predicting academic success in your second language is the amount of formal schooling you’ve had in your first language.3 So in addition to SEI being an ineffective way to learn language, the harmful effects of short-term and pedagogically ineffective solutions span far beyond language acquisition, impacting overall academic success as well.

Because if you’re a student who’s struggling to understand what’s going on in your subject classes — like science or history — then not only are you receiving a subpar language education, but you’re receiving a subpar general education as well. And this can have serious consequences, especially if you’re a high school-aged student who would have to miss two to three courses a day to attend an SEI block. (Take a look at the graphic below for the astounding statistics.)

It’s one thing to believe all students should have the equal right to an education. But is the language that said education takes place in part of the conversation? And how much are students missing out on (potentially years of content) if they aren’t given the necessary language supports that they crucially need?

Finally, outside of academic achievement, what kinds of messages are we sending students when we ban their first language and pull them away from their peers for hours a day? Models like SEI blatantly devalue the importance of students’ first languages and cultures, and limit students’ identity development and opportunities for interaction with their peers. So the potential repercussions of models like these can span far beyond linguistic outcomes.

“But it works for most kids!”

According to one Arizona politician who went through the ESL system himself, “Kids are like sponges… 100% of non-English speaking kids will swim if you give them the opportunity to.” 4

I can’t deny the fact that there are certainly former ELL kids who went through this “sink or swim” process in school, and ultimately came out successful on the other side. And when it comes to stories that we hear in the media, we are really only hear about those high-achieving students who did “swim.”

But what about the ones who sank?

This forces us to ask the question: We can’t deny that “immersion” — really, “submersion” — can work for some students. But at what cost?

I believe that Arizona is in desperate need of a new model for supporting ELLs. Students deserve to learn in a way that is actually research-backed and time-supported — but what they’re getting is an expired model that was strictly political from the very beginning.

I also need to acknowledge that this type of learning environment is not unique to Arizona (although it is true that in terms of US states, Arizona is one of the last states still holding out on English-only education, with California and Massachusetts having repealed similar laws within the last few years).5

In fact, millions of non-dominant language users around the world will never experience an education in their first language, forced to “sink or swim” in a dominant language classroom instead. The longer that these problems of language-in-education remain unaddressed, the longer we continue to underserve generation after generation of students.

Because the reality is this: students should not have to spend years drowning before they learn how to swim.

A final note

Thank you for reading this week’s newsletter — I hope you found it insightful and helpful (especially if you happen to be an Arizona voter — keep your eye on what’s on the ballot).

This newsletter is also a bit different from previous ones thus far, as it focuses more on language in education and politics. So if you found it especially interesting and are excited for more, please let me know — it’s always great for me to hear from you!

If you haven’t already, would you consider subscribing to this newsletter? Your support is a big help to me & really keeps me going! (And for my new subscribers this week — hello! Thank you for your support!)

Thanks for reading, and I’ll see you next week!

Alcaraz, M., Ruiz, R., Moll, L., & Panferov, S. (2011). Perspectives from SEI Teachers Instructing in Arizona's Four-hour ELD Block. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses.

Thomas, W., & Collier, V. (2002). A National Study of School Effectiveness for Language Minority Students' Long-Term Academic Achievement. UC Berkeley: Center for Research on Education, Diversity and Excellence.

May, S. (2017). Bilingual Education: What the Research Tells Us. In O. García, A. M. Y. Lin, & S. May (Eds.), Bilingual and Multilingual Education (pp. 81-100). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-02258-1

Hernandez, R. (2021, March 23). Arizona House Committee Passes Bill To Bring English-Only Instruction Law Before Voters. Fronteras. https://fronterasdesk.org/content/1669145/arizona-house-committee-passes-bill-bring-english-only-instruction-law-voters

Mitchell, C. (2019, Oct 23). ‘English Only’ Laws in Education on Verge of Extinction. EducationWeek. https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/english-only-laws-in-education-on-verge-of-extinction/2019/10

Is there anything coming down the legislative pipeline that addresses a better way to support ELLs?

This is a great write-up, thank you. I remember voting no on Prop 203 and being disappointed at the way things were beginning to change in Arizona. In the 90s, Arizona universities, especially NAU were instrumental in helping to make higher education more accessible and affordable for all the disparate tribes and communities spread across the state through distance learning and classes in languages other than English. The sad irony is that Arizona could be an incredible asset to the revival and spread of so many native languages, but not until "English-first" policies get put to ground.