Unpacking The Mixed Response to the Oxford Dictionary of African American English

(why people feel kinda iffy about it & why this is a pro-ODAAE newsletter)

Recently, the New York Times published an article about the forthcoming Oxford Dictionary of African American English (ODAAE). Spearheaded by Dr. Henry Louis Gates Jr. of Harvard University, this dictionary will document the definitions and origins of English words that come from & are found in African American English. It’s set to publish its first 1,000 definitions in March of 2025.

(You may have heard of a lot of terms being used to describe this particular dialect of American English, including but not limited to: African American Vernacular English, Black Vernacular English, Black Language, Ebonics, etc. In this article, I’m opting to use the term African American English, or AAE, since this was the term preferred by the team behind the ODAAE.)

While my initial response to this news was — “Wow!! Great!!” — I was interested to see that the response from the general public has been… all over the place. Here are the types of comments that I’ve seen on social media and news articles:

This is awesome!

No thanks, this is too progressive. (Another useless performative liberal project.)

No thanks, this isn’t progressive enough. (Focus your energy on issues that matter more in the world.)

I don’t understand why this matters at all — just add words to the normal dictionary.

These responses are intriguing to me because they are a reflection of how AAE is perceived as a dialect in America (if you want to get specific, it would be considered an ethnolect — a dialect spoken by a particular ethnic group).

I think we can distill the confusion down to two questions. One, is AAE a real, distinct English dialect? And second, is it legitimate enough of a language variety to warrant formal documentation via dictionary?

Before jumping in, I want to make clear that I’m coming at this from the perspective of a linguist (who is a mixed Asian American), not as a Black person, speaker of AAE, or linguist specializing in AAE. So please take this all with a grain of salt, and I am very much open to any corrections or clarifications by AAE scholars or AAE users.

1. Is it a Real, Distinct English Dialect?

Some non-AAE speakers are surprised to find out that AAE is not just an amalgam of quirks. It really is its own English dialect, with consistent and distinct features, from grammar, to pronunciation, to syntax, and more.

The following are just a few examples of the many features of AAE (which I’ve lifted directly from Alim, 2004)1 —

Invariant “be” for habitual aspect (“He be actin crazy,” meaning “He usually/regularly/sometimes acts crazy,” Fasold 1972)

Stressed BIN to mark remote past (“I BIN told you not to trust that woman,” meaning “I told you a long time ago not to trust that woman”)

3rd person singular present tense -s absence (“I know who run this household!” for “I know who runs this household,” Fasold 1972)

Negative inversion (“Can’t nobody touch E-40!” meaning “Nobody can touch E-40!”, Sells, Rickford and Wasow 1996)

So beyond its lexicon, which is being documented by the ODAAE, it certainly is a legitimate and widely spoken variety of English. It is consistent, and its usage is well-documented. AAE is a dialect with centuries of history and intergenerational use.

(It’s also worth mentioning that there are way more English dialects out there in the world that many English speakers fail to consider, beyond just American English and British English. Many of these fall into the category of “World Englishes,” and have their own consistent patterns and usages. This includes but is certainly not limited to Singaporean English, Nigerian English, Indian English, Hong Kong English, and A WHOLE LOT more.)

2. Is it Legitimate Enough to Warrant Formal Documentation?

“Sure, AAE has patterns,” you might be thinking. “But is it really worthwhile to make an entirely new dictionary for AAE? What’s the point of that?”

First of all, Oxford has clarified that these words will be incorporated into the main Oxford English Dictionary (OED) as well as the ODAAE. So they will also be part of the general archive of English words, as they probably should be.

But I think there are two main benefits of a separate dictionary for AAE. For one, it provides a clear account of English words that we take often for granted. Secondly, it is a step towards legitimizing how AAVE is perceived in society, fighting linguistic supremacy in the process.

Where Words Come From

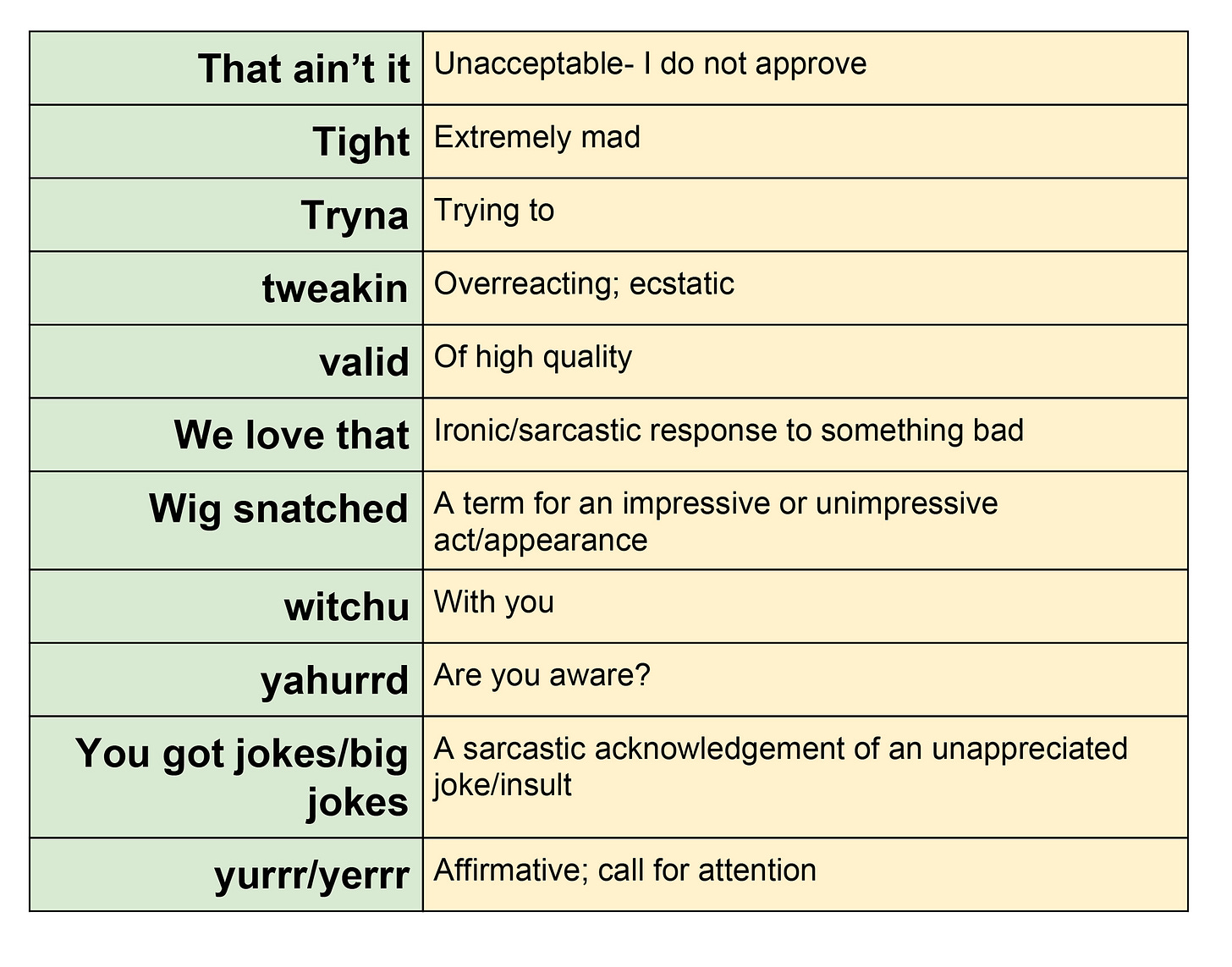

Gen Z is notorious for their creative slang that is sometimes hard for non-Gen Z members to keep up with. No cap. Bussin. Sus. You get the point.

But this slang has to come from somewhere. And a lot of it comes from two communities in particular: the Black community and the LGBTQ community.

“Bussin” is one is example of this from AAE, and one of the terms that will appear in the ODAAE. It’s used as an adjective and participle, and is defined as:

1. Especially describing food: tasty, delicious. Also more generally: impressive, excellent. 2. Describing a party, event, etc.: busy, crowded, lively. (Variant forms: bussing, bussin’.)

Since many of these terms are used in casual, sometimes younger contexts, we default to labeling these as “slang.” But we can’t deny that something about the label “slang” makes it sound less legitimate, less deserving of a place in a real dictionary.

One function of the Oxford English Dictionary that some might not know about is that it doesn’t just give you a definition: it also gives you a historical record. It draws from multiple sources — from books, to newspapers, to other forms of media — to explain how the word has changed and evolved in use over the decades. (The OED is my primary resource for any articles that involve word origins.)

Here’s a look at how the dictionary entries will appear, with both definitions & a historical record2 —

So creating a dictionary of AAE isn’t just like an Urban Dictionary entry of a fleeting slang word that no one will use in a year. It actually provides linguists, sociologists, and generally curious people a comprehensive record of the richness of the English language. Coming at it from the perspective of AAE is a much-needed documentation of the legitimate ways in which the English language has evolved over time.

Fighting Linguistic Supremacy

With the knowledge that AAE is a distinct dialect with its own patterns, structures, and lexicon, we are now forced to ask: what made us question its legitimacy in the first place?

The reality is that AAE has been stigmatized as a lesser-than linguistic form, mischaracterized as being an “informal” or even “incorrect” version of American English. This harmful view has persisted on in American society for centuries now. The aforementioned Alim (2004) essay focuses in on formal schooling as one way in which these prejudices are reproduced.

In another New York Times article on the subject, Tracey Weldon, a linguist at the University of South Carolina, sums up the conflict about AAE aptly:

“It is almost never the case that African American English is recognized as even legitimate, much less ‘good’ or something to be lauded,” she said. “And yet it is the lexicon, it is the vocabulary that is the most imitated and celebrated — but not with the African American speech community being given credit for it.”

The creation of this dictionary forces us to grapple with this tension. How were we socialized into perceiving linguistic varieties that appear to be “non-standard,” not to mention the speakers of non-standard varieties? Alim further challenges us with this:

By what processes are we all involved in the construction and maintenance of the notion of a ‘standard’ language, and further, that the ‘standard’ is somehow better, more intelligent, more appropriate, more important, etc., than other varieties? In other words, how, when and why are we all implicated in linguistic supremacy? (p. 149)

Thanks for reading!

The ODAAE is certainly not a panacea for the linguistic prejudices that swirl around in society against AAE and AAE speakers. But it is one step in the right direction. It affirms the legitimacy of AAE as a dialect. It rightly names AAE as an undeniable force in shaping the present and future of the English language, even for non-AAE speakers. This is something that is worth acknowledging.

What was your reaction when you heard the news about the ODAAE? Are you a speaker of a “non-standard” linguistic variety, and have you faced any challenges as a result? What does linguistic discrimination look like in your community?

Thanks for reading, and I’ll see you next Tuesday!

H. Samy Alim (2004), “Hearing what’s not said and missing what is: Black language in White public space.”

https://public.oed.com/blog/pr-odaae/

This is very insightful. Amazing job Rebecca!

Great article. One of the great changes in linguistics over the last few decades is the recognition that languages and dialects that were once considered inferior versions of the real deal actually have as much subtlety and nuance in their structure as those other languages. To master them takes the same ability as needed to master other languages.

On that subject, a feature of American English that catches me is highlighted in your article when you write "is it legitimate enough of a language variety to warrant formal documentation via dictionary?" That construction sounds odd to my NZ ears, which want to hear "is it a legitimate enough" etc. But in American English it's something you hear a lot. Maybe I'll write a piece on it someday, explaining why my version is correct!