Tucked behind the corner of the Mastaba Tomb of Perneb — the 15-foot structure that greets visitors to the Egyptian wing — lies a modest, fairly unimposing doorway. It’s easy to miss at the sprawling Metropolitan Museum of Art, a four-block long New York institution, and one of my most beloved places in the world.

If you do choose to step inside, you’ll find yourself struck by the quiet majesty of this gently-lit limestone space. There, almost too close to your face for comfort, is an array of intricate Egyptian relief carvings — humans, animals, and a writing system that appears to be art itself.

This is the Tomb Chapel of Raemkai, a rebuilding of the tomb that once laid a pharaoh’s young prince to rest (although it was originally built for an official named Neferiretenes; traces of him still faintly remain).

As you observe the images illuminated on the walls — men hauling nets, herding and butchering rams — you’ll also find meticulously carved hieroglyphs, which in this hushed space, seem to come to life just a little more than usual.

Sometimes they’re nestled between illustrations, narrating scenes. Other times, they’re the main event, like how they brazenly cut through the false door, where the dead pass through to accept offerings from the living.

These hieroglyphs (which as a system, are “hieroglyphic,” not “hieroglyphics”) may initially appear to be orderly and rigid, mathematical in their precision, just as we would expect the ancient Egyptians to be.

But sometimes, they seem to go every which way: reading up and down, side to side. If you look closely, you may even find that the text appears on occasion to be flipped, like a mirror.

And in fact, it is. Hieroglyphs are not as fixed as they may seem, containing a multitude of flexibilities. On Raemkai’s false door, the text blends in seamlessly with the images, mirrored to face the same direction as the figures they accompany.

Just as they captured my attention the first time I stumbled into this sleepy tomb, hieroglyphs have amazed and baffled historians for centuries. Most attempts to crack the code had simply been driven by too narrow of a vision: hieroglyphs are not purely phonetic, nor are they purely idea-based.

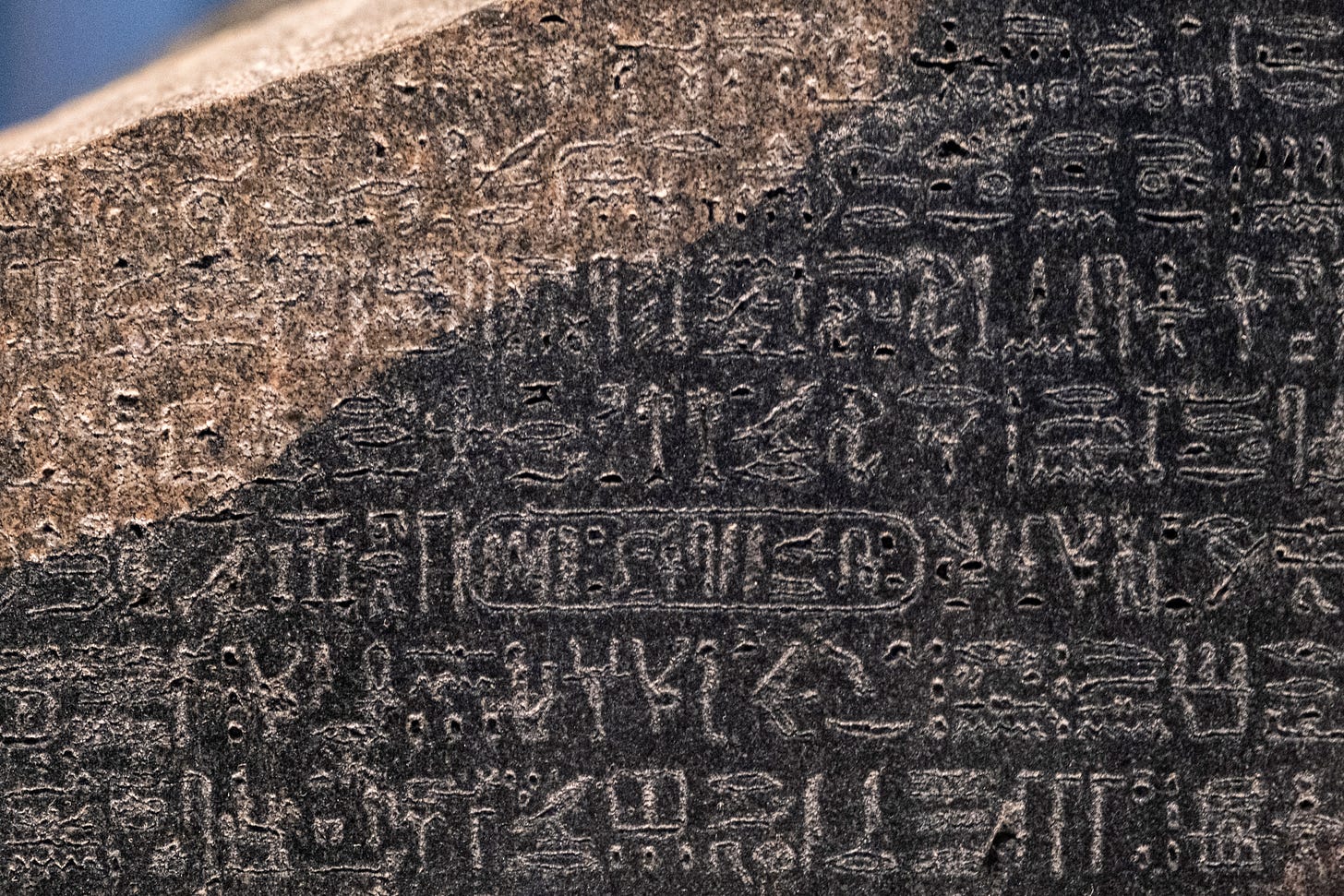

It wasn’t until the crucial Rosetta Stone — and a breakthrough linguistic discovery made by a French schoolteacher, Jean-François Champollion — that this system was finally decoded once and for all.

I can’t help but marvel at this writing system which, unlike cuneiform and Chinese (whose development we can clearly track), seemingly popped up out of nowhere in 3250 BC, a distinctly Egyptian creation.

Complexity and Creativity

Primarily used for monuments and religious texts, and known as the “gods’ speech,” hieroglyphs can generally be used in three different ways.1

Ideograms are used to write the words that they depict. The symbol below, shaped like a mouth, means “mouth.”

Phonograms are used to represent sounds. The same symbol above for “mouth,” which was likely pronounced like “ra,” could also represent the sound “r.” In this character, “door” and “mouth” are combined phonetically to create the word “emerge.”

Determinatives are extra signs which help the reader interpret whether a word should be read as a phonogram or as an ideogram. It can also help point to a word’s general idea or category. In this instance, the walking legs indicate that the preceding “door” and “mouth” should be read phonetically, as the word “emerge.”

Beyond these three categories, there are even more layers of complexity. Phonograms can be uniliteral, biliteral, or triliteral — indicating the use of one, two, or three letters.

A biliteral sign of a coin, for example, would represent two letters — “c” and “n” — and could be used to create words such as “cone,” “can,” and “cane.”

As I learn about hieroglyphs, I am struck by the ancient Egyptians’ deep understanding of language. Like their approach to visual art, which is measured, principled, and scientifically-driven, hieroglyphs systematically utilize multiple dimensions of language to make meaning: sound, semantics, and symbolism, all at once.

At the same time, hieroglyphs’ flexibility meant that writers had the space to be playful and creative with language. This was especially noticeable during the Ptolemaic and Roman times, where new and innovative “spellings” emerged — driven by puns and wit, yet grounded in grammar.

It is this creativity that gave rise to the stunning Ram Hymn at the Temple of Khnum in Esna, where walls of text are written exclusively in ram hieroglyphs, honoring the ram-headed god of fertility, Khnum. (There’s also a Crocodile Hymn, written entirely in crocodile hieroglyphs.)

Stunningly, these texts are not just fanciful drawings of animals in various positions. Rather, they are fully linguistic and fully intelligible — although they certainly require extra effort for scholars to interpret now. Egyptologist David Klotz’s translation of the Ram text is mind-boggling.

Since I can’t make it out to Esna to see those crocodiles and rams in person, in the meantime, I’ll keep wandering through the Egyptian wing of the Met. And if you have a chance to do the same, I hope that you allow yourself to be filled with wonder and awe at the beauty of hieroglyphs — the same way that centuries of scholars once were, and the same way that I was, the first time I passed through that doorway.

Thanks for Reading!

I still have much to learn about the earliest representations of language (and will share my ongoing findings here!), but I love how language allows us to get straight into the minds and lives of ancient peoples. What ancient civilizations or languages are you most curious about?

Finally, if you aren’t already a subscriber, please consider doing so now to receive more newsletters about language, people, and our rich linguistic world.

Until next time,

Rebecca

Allen, James P. Middle Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs. 3rd Ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

Fascinating. You might enjoy this review I wrote on this subject: https://open.substack.com/pub/terryfreedman/p/review-of-the-hieroglyphs-exhibition?r=18suih&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web

common Rebecca W