Lessons from a Literacy Interventionist

(the actual issues I see with struggling readers & why people are arguing about how kids learn to read)

For the last year and a half, I’ve worked as a literacy interventionist in an elementary school in New York City. And it’s given me a pretty vivid glimpse into the debate that is currently raging about how kids learn how to read.

If you haven’t heard about this debate yet, chances are you will soon. Because it isn’t just between teachers — it’s hitting the mainstream. It’s extended to school boards, parent groups, and even the media. The podcast “Sold a Story,” which investigates the history of how literacy is taught in great detail, has garnered millions of downloads. A recent New York Times article on America’s reading wars also sums up the controversy.

The conclusion that many people are coming to is basically this: there is something very wrong with how kids are learning to read.

But how warranted is this claim? Because, it sounds pretty intense. Surely, most kids graduating high school end up literate anyway, right? Are we claiming that all teachers are incompetent and don’t know what they’re doing? (Emphatically: NO.) So why haven’t we resolved this hubbub over something that seems so incredibly intuitive?

A Very Brief Summary

While theories on literacy have evolved over the decades, the main sides of the debate are supporters of two different methods as they are known today: balanced literacy and phonics.

Balanced literacy is a way of teaching kids how to read that emphasizes fostering a love of reading. It hinges more on the assumption that reading is a natural skill that kids can pick up without too much explicit teaching. They don’t totally eliminate the teaching of the sounds that make up words, but also promote other techniques like guessing unknown words based on context, pictures, and “what makes sense.” This is guided by the assumption that good readers employ multiple methods when they encounter an unknown word, and if kids have more tools in the toolbox, they can be more successful readers.

The other side of the coin is phonics. (You might also hear this referred to as “the science of reading.”) This is guided by research showing that kids actually do need systemic explanation of the sounds that make up words. The teaching of these sounds is much more explicit. And in their view, the strategies mentioned above aren’t hallmarks of good readers: they’re the strategies that struggling readers use to get by. For phonics supporters, learning to sound out words is of primary importance.

One of the downsides of this debate is that it’s become highly politicized, for a few different reasons. The holistic and whole-child perspective of balanced literacy generally appeals more to liberals, and George W. Bush’s push for phonics in particular has given it a more conservative association. (This is a super distilled version of the politicization of literacy, but it is important to note, since it has certainly played a big role in how these methods are perceived.)

Explicit or Implicit Learning?

As an applied linguist, this debate is especially interesting to me because we also deal with implicit versus explicit language teaching. The conclusion that I’ve gathered (at least when it comes to second language teaching specifically) is that both implicit and explicit teaching have their place, and students benefit most when teachers utilize a mix of both. (If you’re a language teacher and want more details, let me know in the comments!!).

But unlike language itself, which humans actually have been picking up naturally for tens of thousands of years, literacy is a relatively new phenomenon. Reading and writing systems are purely human fabrications, and globally speaking, while literacy rates have risen over the years, there are approximately 773 million illiterate adults.1 So learning how to read is certainly not a given component of what it means to be a person. Our brains aren’t necessarily wired for writing systems the same way that it’s wired for language.

So if you were to ask me, I’m definitely more in the camp that kids need a little more explicit instruction when it comes to learning how to read.

To back this claim up, here are two significant issues that I’ve observed when it comes to how kids read.

Issue #1: Lack of Phonemic Awareness

One of my small triumphs from this last year was when I really felt like I intervened with a struggling reader in a big, big way.

I was leading one student through a creative writing activity when I made a shocking observation: this student was ending a LOT of their words with the letters “-ah.” Like, teacherah. Pencilah. Computerah. And so on.

I asked this student why they were doing that, and they explained that it’s because those words ended in the sound “-ah.” They proceed to pronounce each word with a little puff of air (like a small “uh”) at the end. Plantₐₕ. Pictureₐₕ. Pikachuₐₕ. Everything ends in “-ah.”

So I decided that if this kid came away from our sessions with no other skills, they would at the very least stop ending all their words with “-ah.”

I conducted a phonemic awareness test on this student and realized that they were struggling with concepts from two grades ago. So we broke down words, really listened to the sounds, and talked about what we were hearing.

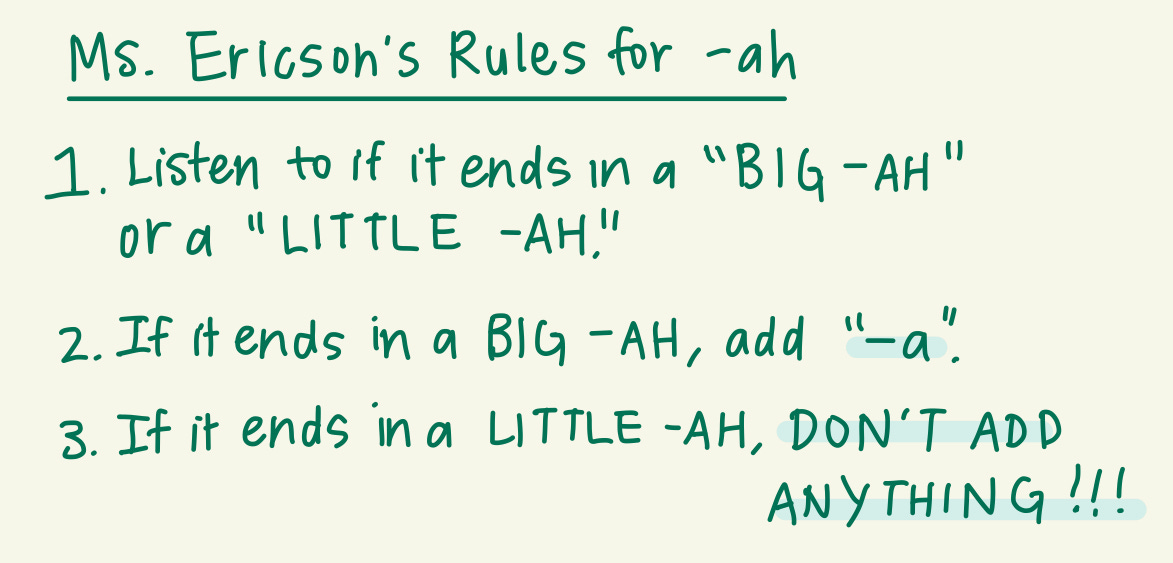

Eventually we got “-ah” specific. We observed how many words ending in what I called a “big -ah” didn’t even have the “h” on the end of them (like koala, pizza, and panda). And if this student was hearing a “little -ah” (or, a word that really doesn’t end with that sound at all), they should NOT include an “-ah.” This culminated in the following handy rules:

Although my student resisted this for a bit, declaring at one point that they wouldn’t remember these rules, I found towards the end of the school year that they actually had stopped this habit, and that gave me a real sense of accomplishment.

So what was the issue that made this student add “-ah” to everything? They were struggling to understand the little sounds that made up words — even making up sounds that weren’t there.

Their lack of phonemic awareness wasn’t a problem that could be fixed from exposure alone. They needed someone to walk them through what sounds were and weren’t there, and how that translated to the page.

Issue #2: Over-reliance on guessing

One of the criticisms of the balanced literacy technique is that they teach students multiple techniques for what they should do if they see an unknown word. And it’s not always sounding it out — students are encouraged to make guesses based on context or based on the picture.

But this method clearly has limitations. Because what will this child do when they grow older and books start to have less pictures? Or what will they do if they’re reading a book about a topic that they have no familiarity with?

I found as a literacy interventionist that my students would frequently employ the following strategy when reading a longer, unfamiliar word: they would say a familiar word of approximately the same length and quickly continue reading (hoping that I wouldn’t catch them).

This resulted in taking sentences like “This was very intriguing to her” and reading it as “This was very interesting to her.”

I would have to challenge them to go back and ask: What sounds do you see inside that word? At the end of the word? Did it match what you said? (“-tion” in particular was a killer, especially if it appeared mid-word).

I worry that kids who guess words (and more often than not — get away with it) are missing out on an important skill: knowing what to do when we encounter words that we have never once seen before in our lives. It’s not enough to just guess a similar word. We miss out on a lot when we do that.

And even as adults, we simply can’t get around sounding out long and unfamiliar words. Just ask my cousin, who is a nurse and frequently encounters long names and terms like “esophagogastroduodenoscopy.” No strategy can help you figure that out, other than sounding it out little by little, right?

An intriguing conclusion

While I’m generally making a case for explicit reading instruction, I have a confession to make. According to my parents, I learned how to read largely on my own. I was reading happily before I started kindergarten while my parents looked on with some confusion.

But one of the key resources that taught me how to read was my favorite PBS show at the time, Between the Lions. And at least from what I remember, it was pretty explicit, with each episode focused on particular letters and sounds.

I still remember some of the teaching from that show (almost always rooted in music, and I think that was really the key for me). Like the song, “When two vowels go walking, the first one does the talking.” Or even the song that literally just taught you how to spell the word “chicken” — “C-H-I-C-K-E-N, That’s the way you spell chicken.”

So while in my parent’s eyes, I had “picked up” how to read without much assistance, I know for a fact that this show played a role in teaching me the letters and sounds I needed to make sense of it all.

It would be remiss not to acknowledge that some kids really just are able to learn how to read faster, picking up the sounds and systems of letters a little more easily. But I believe that the vast majority of kids need to be taught more explicitly (not to mention kids with learning disabilities like dyslexia!).

So as this debate rages on, I hope that there are positive changes up ahead in how we teach kids to read. Because there are a lot of kids that are getting left behind, many more than we know.

Thanks for reading!

Thanks for reading this week’s edition of Everybody Talks! Do you remember how you learned how to read? Was it effective? Did you (or do you still) struggle with any aspects of reading? Let me know in the comments below.

On a side note, I recently received my MA in Applied Linguistics! So now I can feel better about actually calling myself an applied linguist (with less of that good ole imposter syndrome). Woohoo!

Thanks for reading and I’ll see you next Tuesday!

https://uis.unesco.org/en/topic/literacy

Hi, Rebecca! I stumbled upon your site from Victoria and Lou! I absolutely love this post because it made me reflect on my own teaching background.

As an EFL educator in Japan, my students (4th through 6th grades, low-beginner levels) lack phonemic awareness as well and since I rotate around schools in my city every year, I find it really tough to create something sustainable for them! I feel like I overcompensate by pointing out the differences in the phonetic system and syllable structures whenever I can. I feel that explicitly teach students about different sounds and their distinctions could help improve their awareness. As for implicit teaching, I try to use songs, rhymes, and chants to encourage playful interaction with the language while focusing on pronunciation accuracy. Other than that, I'm stumped! Is there anything you'd do differently?

Congratulations on your MA! I'd love to read more of your insights on how to combine implicit and explicit learning when teaching. 😊

A couple of words haven't made it in this sentence: "there are approximately 773 [millions] illiterate adults [in the world]". Thankfully you shared your source!