Scholars estimate that between fifty and ninety percent of the world’s spoken languages may be extinct or seriously endangered within the next 100 years. In other terms: approximately every 40 days, one language is lost, and this rate will only increase over time.1

But why do dying languages even matter in the first place? Is there really a case to be made for linguistic diversity in our modern world?

Myth #1: Language death is natural.

“Wait,” you might be asking yourself. “Hasn’t she written about the inevitability of language change on this very newsletter? What a hypocrite!”

Hold your horses, because there is an important distinction to be made here. Yes, languages change and evolve over time - all languages! Sometimes we simplify forms because it’s easier to say. Sometimes sounds that used to be distinct morph into one sound. Some words will broaden in meaning or perhaps do the opposite. Some languages will change as a result of coming into contact with other languages.

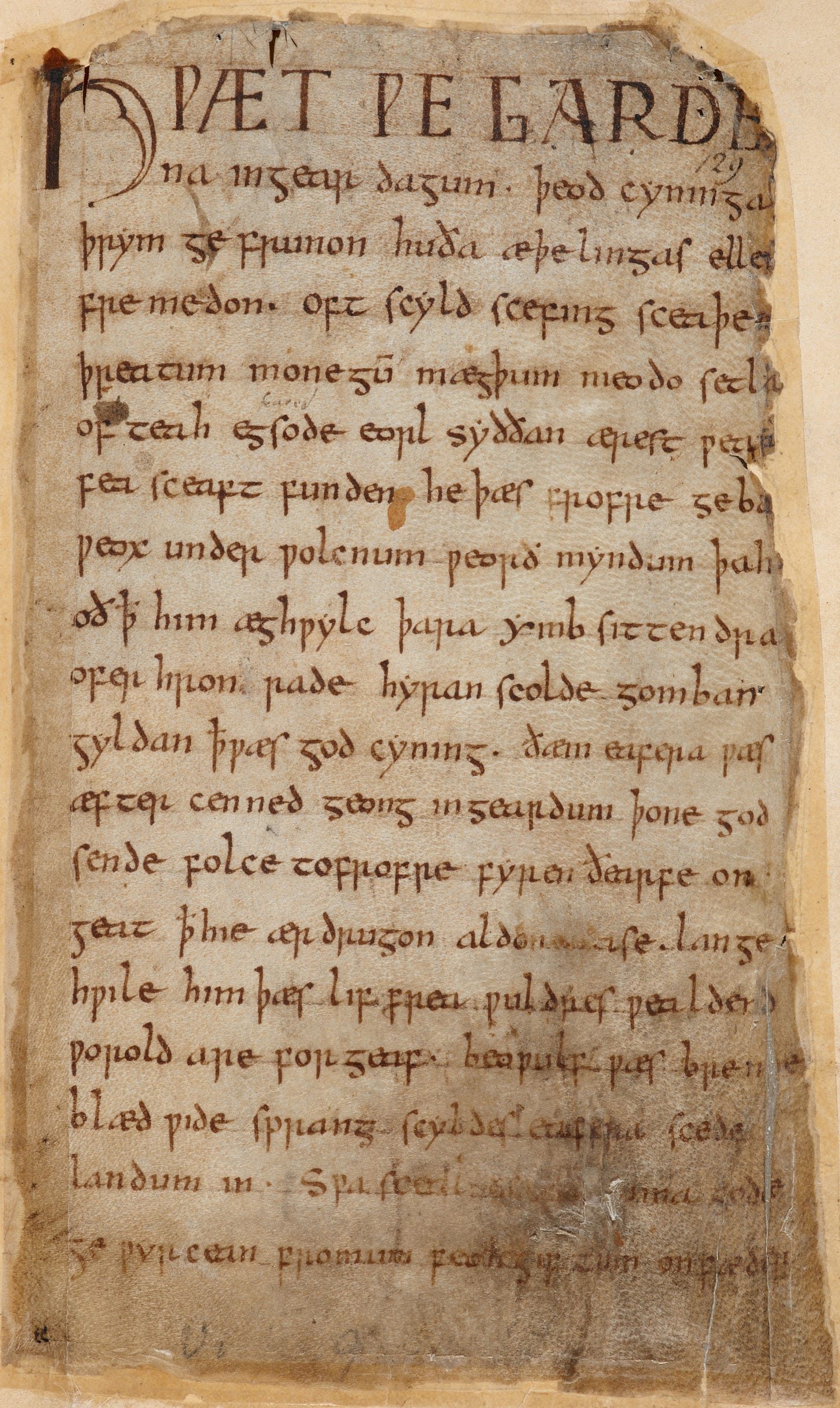

It’s clear that viewing language as a static and unchanging monolith is certainly misguided. (Try and read the snippet from Beowulf below and this will become exceedingly clear.)

But when it comes to languages going extinct, we’re talking about something totally different. And it’s easiest to see that difference when we get to the heart of it, by asking the following question: why?

When we lose a language, it’s almost never a process of people just choosing to speak the dominant language on their own accord. It’s almost never a community collectively deciding that their language is just too complicated, and opting for a language with simpler forms. And it’s nothing like the process of language change, where sounds shift, meanings expand, and sentence structure morphs. What makes a language die?

To think about what language loss entails, we need to situate that language in its appropriate context — and that means, with the people who speak it. And when we do that, it becomes evident that language loss is also a loss of cultural and intellectual diversity, “in which politically dominant languages and cultures simply overwhelm indigenous local languages and cultures.”2

If you need an example, just look to North America’s history of residential schools, in which generations of Indigenous peoples were violently removed from their homes and forced to stop speaking their home languages. This has resulted in the severing of the intergenerational transmission of languages that typically takes place in the home, thus resulting in community-wide language loss.

And it’s not just North America. Kayardild, the Aboriginal language of Bentinck Island in Australia, had its “fate sealed” when missionaries in the 1940s displaced the entire population to another island. Parents were separated from their children in dormitories, and children were punished for speaking their home language. In just one generation’s time, the Bentinck Islanders went from monolingual Kayardild speakers to never again having a child fluently speak Kayardild.3

Darrell Kipp sums up the long-term generational effects of language loss for Blackfoot speakers as such—

The history of tribal language oppression is well documented, but what is not given enough credence is the effectiveness of the eradication processes used. In our tribe, the negative conditioning was so successfully ingrained that the taboo against speaking our language remained fresh in the minds of even second and third generation non-speakers of the Blackfoot language.4 (emphasis mine)

So when a language dies, it’s not the same as natural language change. Take one look at the surrounding circumstance and this becomes abundantly clear. Often times, it is better described as forcible, traumatic, and — at the bare minimum — unjust.

Myth #2: Modernization necessitates monolingualism.

Some people are shocked to find out that premodern France was actually quite linguistically diverse — in fact, only about 1/10 of the population spoke French!5

But when the French revolution rolled in, regional languages were increasingly viewed as relics of the old regime. The French revolutionaries believed that standardizing a national language was key to their country’s success — and the existence of local, regional languages had the potential to impede this progress.

Unsurprisingly, this sort of idea prevails to this day. In our rapidly globalizing world, some argue that a unified, common language might be key to strengthening global ties — politically, economically, and socially. Some people even go one step further to argue that fighting so hard to keep minority languages alive may keep the linguistically marginalized even more marginalized.

I would challenge this assumption with one question: Why does the use of a dominant language necessitate the loss of non-dominant languages? This kind of thinking assumes that monolingualism is the only way to go.

But is it? In today’s world, it’s surprisingly common for speakers of minority languages to speak multiple languages. (Surprisingly common, like, millions of people around the world.) This can include languages of wider communication (LWCs) to interact with speakers of other languages in the region, national languages, and global languages. (My friend from Malaysia grew up speaking Cantonese and Mandarin with his immediate family and community, Malay with his wider community, and also learned English in school. And I’m pretty sure I’m missing one or two more languages!)

So if the human brain required us to pick only one language, with no space for any others, then we would be having a different conversation here. But not only is multilingualism achievable, it is the living reality of millions of people around the world. Why would we need to pick just one language and ignore all others in order to modernize?

Myth #3: Language death isn’t a big deal.

I’ll cut to the chase. It is a big deal. Because language is not just a forgettable relic, trivia item, or dispensable artifact. Rather, it embodies and encodes a specific way of thinking and living. It is intimately tied to its users and the communities who have spoken it for hundreds (or thousands) of years. It is an invaluable part of the story of humanity.

And because of this, the sting of language loss is a very real experience for communities and individuals around the world. It would be naive to minimize that pain and rewrite the story of language loss as being a natural or unimportant thing.

(I wrote about a similar emotion just from not being able to use Chinese in my daily life. Imagine the depths of pain of community-wide loss!)

For proof of this, just look at communities who are undergoing language revitalization (a very effortful, emotional, and difficult process). Darrell Kipp sums up why this process matters for Blackfoot speakers:

The promise tribal language revitalization offers is reconciliation; a renegotiation of reality and a restoration of an intellectual beauty possible in the ocean of tomorrows. We must work to regain what never should have been taken away without permission... (emphasis mine)

Linguistically speaking, it’s also a big deal for another reason. Studying the intricacies of the world’s linguistic diversity gives us much deeper insight into the human language faculty, which we still have much to learn about.

One example of this can be found right in the aforementioned Kayardild. Evans (2010) points out that while famous psycholinguists Steve Pinker and Paul Bloom claim that there aren’t any languages that would use noun affixes to express tense, Kayardild does just that, marking tense on both nouns AND verbs.

Languages like these expand our worldview and challenge our assumptions of what language looks like — in this case, even assumptions in Chomsky’s theory of Universal Grammar (gasp!).

So when we lose a language, we’re not just losing some vocabulary words that don’t matter because we have words for those same things in English. (And actually, a lot of the times we don’t. For more on how linguistic diversity supports our understanding of our environment and is intimately tied to creating a sustainable world, click here. It’s one of my favorite hidden gem articles!)

But when we lose a language, we lose a way of knowing, being, and interacting with the world around us. We lose a valuable component of our own humanity, which isn’t completely impossible to get back, but is really, really hard to. And losing a language is not an unemotional, impersonal process — it is always intimately tied to the people who speak it, or who were denied the chance to speak it. That most certainly matters.

Thanks for reading this week’s edition of Everybody Talks! I realized it’s been a while since I’d written about endangered languages, so I hope you enjoyed this piece.

See you next Tuesday!

Simons (2019) - Two Centuries of Spreading Language Loss

Hale (1992) - Endangered Languages: On Endangered Languages and the Safeguarding of Diversity

Evans (2010) - Dying Words

Kipp (2009) - Encouragement, Guidance and Lessons Learned: 21 Years in the Trenches of Indigenous Language Revitalization

May (2016) - Language Imperialism and the Modern Nation-State System

Thank you for that write up. Found out 40 years into my life that my Maternal Grandfather was 1/2 Ojibwe. Which gave foundation to why when he managed Indigenous schools here in the PNW he never punished his students for speaking their language.

My Paternal Grandfather did Rangeland Management for the UN; at the time, his work helped the Maasai avoid being forced from their lands. As they have been for the last decade. Most recently for a UAE based hunting/tourism company.

If anyone wants to learn Ojibwe

https://ojibwe.lib.umn.edu/about-ojibwe-language

Zhawenim miziwekameg

Language *creation* is the other side of this coin. I believe Attaturk helped standardize Turkish in the roman alphabet and made some other changes to help unify the far flung turkish peoples. To my knowledge Indonesia has done the same thing. Tanzania as well? Im sure there’s more examples than first meet the eye.

Hebrew was I think considered a “dead language” (not an extinct one) until it was revitalized by the modern state of Israel.

Your point about monolingualism not being necessary is a good one. The Philippines has almost as many languages as islands, and most people there (to my limited knowledge) seem to be fluent in the national language Tagalog, a local language like Bisaya, and at LEAST English but frequently several others.

I say all this to reinforce and peovide examples of things you discussed in the post.

Language serves as a cultural passport--when the language has died the culture has died, and a section of the rich tapestry of human culture is lost forever. Languages can be revitalized, languages can be invented, but both serve to preserve or define a current culture into the future. There is nothing that can be done once the language, culture, and people are extinct.